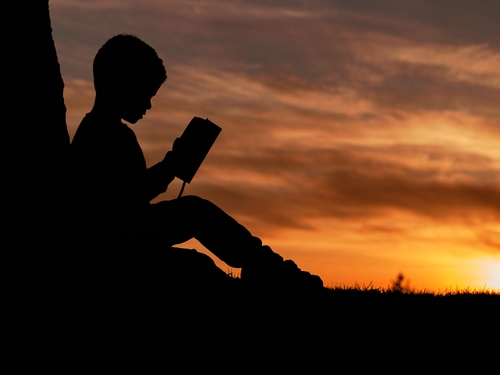

"Power resides where men believe it resides," said the teaser for Season 2 of the HBO series A Game of Thrones, which began airing this last Sunday night. "It's a trick, a shadow on the wall": a fitting epigraph for a postmodern fairy tale. George R. R. Martin has written five books so far in the series on which the TV show is based, the most recent of which, A Dance with Dragons, appeared last summer and immediately topped the bestseller list. Martin's take-no-prisoners realism was evident early on: "When you play a game of thrones you win or you die. There is no middle ground." There is power and there is death, there is king and there is pawn. There is such a thing as honor and valor, but these are secondary, maybe tertiary, to surviving the day. As he writes of one of the heroes of old: "Rhaegar fought valiantly, Rhaegar fought nobly, Rhaegar fought bravely. And Rhaegar died." Martin has been compared to Tolkien. The depth and richness of his world make that claim plausible. In every narrative nook is another mystery, another layered plot for conspiracy enthusiasts to savor. That, at least, is part of the attraction of the series: its inscrutable narrative density. Yet in many respects, Martin's stories have more in common with Machiavelli's Prince than with Tolkien's tales of Middle Earth. Political realists have been quick to catch on to this affinity—Foreign Policy even ran a feature on Martin's realism and its insights for international politics. When asked if he thought his books were too cynical, Martin simply responded "they are realistic." Read the entire article at Books & Culture.

The Return of the Dragons

April 2, 2012

Father Raymond J. de Souza: Whither the religious left?

Much has been remarked about the new leader of Her Majesty’s loyal opposition, Thomas Mulcair, and his desire to move his party to the centre, or the centre-left, or the left-of-centre, recasting them as moderate progressives, or progressive moderates. Whatever the position may be called, will there be room in it for the religious left? For those who are not paying attention, religion is thought to be the exclusive province of the political right. Yet the most religious caucus in Parliament today is that of the Green party, where 100% of its members (namely, Elizabeth May) are recent theology students aspiring to ordination. More broadly, clergy in Parliament are almost always on the left. A few months back, I launched a new magazine called Convivium: Faith in our Common Life. In our first issue, we had NDP stalwart Bill Blaikie, one of Canada’s longest-serving MPs and an ordained United Church minister, write about the social gospel roots of his party. At the same time I wrote that Jack Layton’s defeat of Blaikie in the 2003 NDP leadership convention marked the vanquishing of the social Gospel tradition by a new leftist politics — urban, socially libertine and aggressively secular. In our current issue, Blaikie vigorously objects to my “premature obituary†for the social gospel tradition. I sought out Bill Blaikie to write for us not only because he was a rare combination in Parliament — electorally successful, intellectually sophisticated, and thoroughly decent — but because he tells a story that is critical to understanding the role of religion in our political history, and the present possibilities of the same. His defence of the social gospel in our magazine is made at greater length in his recent very worthwhile book, The Blaikie Report: An Insider’s Look at Faith and Politics, which should be in Mulcair’s transition dossier. Thomas Mulcair does not come from Layton’s downtown Toronto, but his Montreal constituency is likewise a long way from the prairie social gospel championed by clergymen such as Tommy Douglas, J.S. Woodsworth, Stanley Knowles and Bill Blaikie. That tradition was economically interventionist, even statist, but had plenty of room for culturally conservative voices. When people speak about Mulcair’s moderation, it appears to mean becoming rather more centrist on economic issues. To the extent that progressive parties have done this — Jean Chrétien’s Liberals, Tony Blair’s Labour — the portside balance to this centrist shift has been to adopt ever more extreme social libertinism on cultural issues. It’s early days yet for Mulcair’s NDP, and he may well chart a different course. Yet with a caucus filled with MPs from secularist Quebec and almost no one from the Prairies, one expects that the religious left will be a muted presence. Consider Paul Dewar, recent candidate for the NDP leadership. Heir to a famous Ottawa political name — his mother was a formidable mayor — Dewar has told faith and politics author Dennis Gruending that about 75% of his public positions were shaped by his Catholic faith, and 25% by the social democratic tradition. But in his recent book Pulpit and Politics, Gruending relates that Dewar prefers to mute his own voice: “I am prepared to talk openly about faith in [academic] settings. But when speaking in a political capacity I am reluctant to do so because I fear I could be misunderstood and I do not want to use religion to score political points.†In general, politicians running for office are eager to score political points. Perhaps Dewar keeps quiet about faith because he thinks it would give him an unfair advantage. Or perhaps it is that his party and the general political environment make it a liability, rather than an advantage? The NDP is quite a different party than it was a year ago, let alone 10 years ago. Under a new leader in a largely new caucus, its immediate task will be to define where it fits on the political spectrum and what it has to offer to Canadians. That is a more important task than the daily tactics of partisan jousting. Drawing upon its now 50-year history, the New Democrats will have to decide whether the long social gospel tradition is a heritage to be embraced, or to be discarded. Religion is ever so much bigger than politics, and it does have a contribution to make to the political sphere — and not just on one side of the aisle.

March 29, 2012

Gafuik: Here’s how government can help us do better

Nicholas Gafuik covers the recent Manning Networking Conference, and highlights Cardus charitable research in his latest piece in the Calgary Herald: Sound public policy, even when well implemented, is not always enough to produce the desired outcome. Public policy is necessary, but not sufficient. Government alone is not enough. The annual Manning Networking Conference took place in Ottawa earlier this month. The theme was government as facilitator. The annual barometer released at the conference confirms again that Canadians are skeptical of big government and prefer government as a facilitator. Read the rest of his commentary here.

March 25, 2012

Cardus research profiled in Hamilton Spectator, “College of Trades to regulate thousands of workers”

A new College of Trades has an ambitious mandate to regulate about half a million workers as the province takes a stab at reforming an apprenticeship program that originated decades ago. ... In April and September last year, CARDUS, a Hamilton-based think tank, released two reports critical of the college and its mandate. Brian Dijkema, one of the authors of the September CARDUS report, said the problem begins with the lack of research upon which the legislation was based. The report is also critical of the fee structure, which it suggests will require more compulsory trades and possibly, maintain the status quo on ratios. “In the absence of clear criteria and evidence by which the college shall determine compulsory versus voluntary certification, the possibility that trades will be made compulsory for the purpose of funding the college’s activities should give us pause,” the report concluded. CARDUS suggests membership fees will increase to as much as $100 – currently it costs only $40 to register as an apprentice. Read the entire article here.

March 10, 2012

Renew conviviality in Canadian culture: an interview with Peter Stockland

B.C. Catholic does an interview with Peter Stockland, publisher of Convivium. Read the interview here.

March 2, 2012

Private Religious Protestant and Catholic Schools in the United States and Canada

To read the full article, click here .

March 1, 2012

Government debates how to encourage charitable giving

Christian Week covers Cardus, and other, presentations to the finance committee of the House of Commons. Read their coverage here .

March 1, 2012

How the Berenstain Bears enhance the Ten Commandments

I love the Berenstain Bears. I do not say loved, though I have not picked up and leafed through a book in a decade (or two), because love - as physicists say about energy - never really dies, it just transforms. Not all transformations are beautiful, but the Bears, their simple tree house and almost silly moralisms have stuck with me. The news of co-creator Jan Berenstain’s passing has only reminded me that I love them still. I learned things from the Berenstain Bears I’m not sure the Bible ever quite made clear. The Bible was full of stories, my Sunday school teachers told me, but not particularly good ones, if I was to be honest. There were a few in Joshua, with horns and fighting and some devilish scheming. And, obviously, there was the book of Revelation, which saw me through many, many sermons with its dragons and beasties and general apocalypse. Jimmy, my best friend, was good enough to note that Ezekiel also had some especially exciting bits. But by and large it was not the exhortations of Moses’ Decalogue - “Thou shalt not steal†and “Thou shalt not kill†- that stuck with me. Stealing and killing, after all, were pretty dastardly things, and at least a few commandments didn’t make any sense to me at all. I would later come to find these ones rather tricky. Read the entire article at Think Christian.

February 28, 2012

Tell Your Story, Tell It Well

Facebook bums us out. That news set the internet ablaze (or at least a-twitter) early last year, when a study in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin found that subjects persistently underestimated how dejected their friends were---which made them more dejected in turn. Slate describes the origin of the study: [Lead researcher] Jordan got the idea for the inquiry after observing his friends' reactions to Facebook: He noticed that they seemed to feel particularly crummy about themselves after logging onto the site and scrolling through others' attractive photos, accomplished bios, and chipper status updates. "They were convinced that everyone else was leading a perfect life," he told me. Read the rest of this article at the Gospel Coalition here.

February 27, 2012

Media Contact

Daniel Proussalidis

Director of Communications