In a recent column, The Globe and Mail's Doug Saunders tackled British Baroness Warsi's concern for the place of faith in the public square head on, concluding that "the problem in public life isn't Islam, it's religion itself." This came about because the baroness, a Muslim who is chair of Britain's Conservative Party and a cabinet minister in Prime Minister David Cameron's government, is at odds with a recent High Court ruling that the practice of prayer during municipal council meetings (and, by extension, in Parliament itself) is unconstitutional. While the baroness and many others denounced the ruling as the imposition of "militant secularization," the column upholds the view that faith ought to be a private matter with no presence in the public square. It is possible to reach a different conclusion, however, with the understanding that excluding faith from society's public square creates the emptiness that fuels the fires of the fundamentalism – both secular and faith-inspired – some would prefer to hide from view. Secularism is not the settled, intellectually stable public project that many suppose. It is not at all clear that religion is poisonous to Canadian public order, or even not implicit to it. Our Constitution literally says otherwise, and it is questionable whether the stark secularism of a political order with no metaphysical bias about the nature of human kind is even possible in a democratic society. Like Britain, Canada was founded on certain values and principles it still upholds in law and government, values that cannot be demonstrated by naked, rational proposition. Those values come from somewhere. Call it religion. Call it the veil of ignorance, the creator spirit or a consensual contract of cosmopolitan creatures. Still, we believe it. We can't prove it, like a math problem. It's just something Canadians believe – theists and atheists alike. Now and then, we actually die for these things. We have, globally and historically, maintained highly contested, remarkably precise beliefs that are anything but straightforwardly secular, i.e. untainted by faith. The very word "religion" and the separation between the sacred and the secular in public order is itself an invention. The word religion – religio, in Latin – was rarely in use prior to the Reformation. More than a few thinkers have noted the irony of secularism as itself constituting a de facto "religious" system of thought, which defines how and why we can believe things, and where we can talk about them. As some might put it: a secular atheocracy. The utopia to which this argument aspires also ignores the role of faith as an incubator for commonly held social virtues. Common knowledge of the good religion inspires is the baby that goes out with the bathwater when it's banished from the public square. That "square" is the common ground upon which societies meet. In liberal democracies, it's where their ideas mesh, clash and are ground by the polity into compromise. That, in fact, is true secularism: a place where all influence and none dominate. Yet when people's most deeply held beliefs are banished from that public square, they no longer have a meeting place. Without that, the more likely it becomes that those ideas – uncontested – default into fundamentalism and sectarianism. Religion is here to stay, and most sociologists and international relations scholars know it's true. It is pitiable that the crutch of secularist mythology is being yanked prematurely from our public debate, but to meet the challenge of global politics, we need to stop asking how to keep religion out, and start asking what we believe, and why. Religion won't stay out – keeping it so will only fuel those who would seek to radicalize it. Today's question is not about silencing newcomers' beliefs, but about what we believe, what is up for debate and what is not. That, I think, is just good old-fashioned politics.

Beware the secular atheocracy

February 22, 2012

Some politicians just can’t understand what’s good for the goose…

Politicians given enough rope will invariably hang themselves, figuratively speaking of course. Such is the case with Parti Quebecois justice critic Veronique Hivon, whose clamor for legalizing euthanasia and assisted suicide should, if there is any justice, now be choked off for good and all. Madame Hivon came hard out of the chute to condemn Quebec Tory Senator Pierre-Hugues Boisvenu for his recommendation, later withdrawn, that our most notorious convicted killers be left alone in their cells with a length of state-supplied rope. Senator Boisvenu’s call for our worst criminals to receive public assistance in committing suicide, Hivon said, was not only outrageous and shameful but should disqualify him from speaking on justice issues for the Harper government. She demanded his immediate removal from the parliamentary committee currently studying the omnibus overhaul of the federal criminal code. Despite the reputation he has as an advocate for victims’ rights, and despite the caveat of the suffering he endured after his daughter was raped and murdered, Boisvenu’s suggestion was more than unacceptable. It was morally repulsive and just plain foolish. At a purely practical level, the record of homicidal maniacs suggests they would be far happier committing homicide than suicide if left with a stout length of rope. A homicidal maniac takes up the habit, after all, through an unwavering belief in the primacy of his own existence and the dispensability of others (a characteristic he shares, curiously, with the most genteel advocates for population control). Morally, of course, it is repugnant for the state to cold-bloodedly kill even its most heinous criminals. Seeking to evade responsibility by substituting self-execution for capital punishment merely adds cowardice to injustice. Had Hivon not become entangled with advocates of assisted suicide and euthanasia, she would have been perfectly justified in her criticism of Boisvenu. But she is a primary force behind the special commission that spent a year holding hearings across Quebec on legalizing medicalized killing. The commission is expected to release a report on those consultations, with recommendations, at the end of February. If the report opens the door to state-sanctioned medical killing of the ill, the weak, the vulnerable, the elderly, it will be a trap door under Hivon’s feet, or at least her credibility. It will be proposing the same moral formula as underlay Boisvenu’s recommendation: that human beings deemed of no use to society should be disposed of, if not aggressively by the state, then with a push and a nudge from the public guiding hand. The sole difference is the means of killing. Boisvenu wanted the rough readiness of a rope. Presumably, Hivon would opt for something more esthetically refined. What might that be? A needle in the arm? We all await the modalities with bated breath. Most damning of all to her case is her justification, at a press conference in December 2009, for pushing Quebec’s National Assembly to create the special commission and stimulate debate about legalizing medicalized killing. Quebecers, she said, wanted to talk about the issue. Quebecers needed to talk about it. And, standing beside PQ leader Pauline Marois, she insisted it was her duty as a representative of the people to take the argument to the federal government and demand it drop Criminal Code prohibitions against euthanasia and assisted suicide if that is what Quebecers want. “We want to listen to what Quebecers want, what they need and, once we arrive at a consensus, then it would up to Monsieur Harper and his government to give an answer to what the Quebec population has asked for. Let’s hope they (will) be as open-minded as possible because saying ‘no’ to what we will be asking for will be saying ‘no’ to what Quebecers have asked us to ask him,†she said. Under that convolution are two staggering presumptions. One is the implicit assumption that Quebecers would, indeed, ask for medicalizing killing, otherwise there would be nothing to which Harper needs to say “no.†The second is that popular sentiment should be sufficient grounds for the state to legalize health-care executions, or at least defer to publicly funded self-immolation. Quelle horreur, however, when Boisvenu made exactly the same claim apropos of the prison system. Then, Hivon insisted, he was not just wrong but should be condemned for even trying to provoke the debate. A rope, stretched to its logical end, always snaps back.

February 14, 2012

Faith Exchange: Religion and the parental prerogative

What are the limits to raising our children as we see fit? Every parent, child, teacher and neighbour can relate to the question. It's by no means a religious issue alone, but Canadians have seen it in the news lately with strong links to faith. A few examples: In Kingston, Ont., three members of the immigrant Shafia family were convicted of murdering three daughters (and another female relative) who challenged their father’s strong cultural and religious beliefs about their upbringing. In Quebec, parents of various stripes have revolted against the province’s mandatory “ethics and religious culture” school course, which is seen as either too respectful of religion or not respectful enough. In British Columbia, police and the courts have probed questions of child trafficking and abuse related to underage polygamist “marriages.” In Ontario, Catholic school boards have struggled to reconcile church teachings with government efforts to fight bullying of gay students. Almost every Canadian would agree that parental rights stop short of killing one's children, no matter what the creed. But clearly there are many grey areas in this debate, which Faith Exchange panelists have convened to discuss. Guy Nicholson: Thanks for joining us today, panelists. Have you ever found yourself in a position of parenthood where society's requirements conflicted with your faith? Peter Stockland: Years ago, we were involved in a bitter fight over keeping our kids' school francophone and Catholic in Alberta. There was a lot of pressure to have it run as a public school. This was in Alberta, where we had the constitutional right to French language and Catholic education. Even Premier Ralph Klein got involved, asking, "What is a Catholic paper clip?" as if it was all about resources. Our response was that our kids did not have a francophone head and a Catholic head. They were francophone Catholics. Point finale. Lorna Dueck: Yes, I have. When my children were young, I protected and steered them away from things in society that I felt conflicted with the character of Christ. I made a bubble of warm, fuzzy, perfect world around them, or at least I tried to maintain that façade for a few of those wonderfully simple early years. Sheema Khan: We have three children, ages 9, 14 and 15. They have attended a variety of public schools, private non-religious schools and private Islamic schools. We have not faced any "dilemmas" regarding school requirements that may be at odds with our faith, at least not yet. Or if we have, I can't seem to recall them, since they have been amicably resolved. For our two older kids, we have welcomed the classes having to do with sex education as an opportunity to speak further, in private, at home, about moral teachings having to do with intimate relationships before marriage. I can only recall my own experience as a child of immigrants growing up in Montreal, when we were required to recite the Lord's Prayer in public school. My parents instructed me simply to keep silent (since the prayer was not part of our belief system). One year, when my two older children were in a private (non-confessional) school, there was a kerfuffle because one or a few parents objected to a Christmas play, whereas we fully endorsed participation by our children, so they might learn from and participate in the customs of such an auspicious holiday. Guy Nicholson: I was thinking about the Lord's Prayer when I was preparing for this discussion. I think that even if you believe strongly that prayer shouldn't be mandated in secular public schools (which I do), there's a lot to be gained from Sheema's very tolerant approach. Howard Voss-Altman: While I respect Sheema's very tolerant approach, I fundamentally disagree with it. In a public-school setting, such prayers are an establishment of religion by the state and – by design – are meant to exclude minority religious beliefs or the non-believer. In a private-school setting, it is up to the individual parent to determine the limits of religious tolerance. Personally, as a religious minority, I would not want my children to be forced to remain silent (and suffer the potential harm of social exclusion) while others were praying. I would not choose such a school for their education. Guy Nicholson: Absolutely – I don't think tolerance should be a substitute for advocating the right thing. It's just a wonderful attitude to make the most of what life gives you – to use something like that as a learning opportunity. Howard Voss-Altman: I'm not quite sure I see your perspective. Do you think it is (or would be) appropriate to be exposed to the Lord's Prayer in a school setting? Is that the learning opportunity you are referring to? Guy Nicholson: No, I don't at all think it was appropriate to have prayer mandated in school. I'm glad those days are over. I do think her response to it was great – her family used sex ed as an introduction to home discussion, they respectfully declined to participate in the prayer and they used a Christmas play as an opportunity to learn about another faith's customs. Sheema Khan: We were brand new to Canada, and at the time, we did not know our rights. Some children were excused. I actually enjoyed listening to the Lord's Prayer, because portions resonated with my belief in one God (Allah, in Arabic) – reflecting on the magnificence of God, being grateful for provisions, asking for forgiveness, forgiving others, asking for protection against evil. I loved starting my day off in that frame of mind. I never felt socially excluded. I had Christian friends who would mumble the words, and not take it as seriously as I did. However, I do agree that for a state-sponsored inclusive system, there should be no exclusion based on faith. Howard Voss-Altman: Thanks for the clarification. I should note that our children go to the Waldorf School here in Calgary, where "spirituality" is a very high priority. This often results in participation in Christian festivals, which our children have done as an opportunity to learn about other customs. However, all prayers are pan-spiritual, noting God as the creator and sustainer of the Earth. My issue has always been with sectarian prayer in a compulsory setting. Peter Stockland: The flip side of asserting the truth of your own faith has to be total circumspection in putting others in a situation of feeling obliged to recite your prayers. In addition to being inhospitable, it is sacrilegious on all sides. Prayers are not just to be said. They are to be believed. And if they are not believed, they should not be said. Guy Nicholson: Are you just talking about at school, or does that extend to the home? Aren't children put in a position of feeling obliged to recite a parent's prayers? Howard Voss-Altman: In a word, Guy, yes. That's how all values – religious and non-religious – are transmitted. A family is not a democracy, at least not until the children reach an age of majority. Until then, it is up to the parents to inculcate our values. Choice is a luxury children will have at a much later stage in life. Peter Stockland: There is clearly a difference between forming your own child on the faith of the family, teaching that child what prayers to say and how, and imposing them on a non-family member whose faith is already formed or in the active process of being formed differently from your own. Guy Nicholson: Panelists, can you imagine a situation in which you might break the law in order to parent according to your beliefs? Lorna Dueck: Well, that would depend on how distorted the law could become. Yes, I think parents in less than democratic countries do this, historically parents have had to show children a better way and future than a government might limit, and given that parents bear the responsibility for raising a child, yes, I think parenting overrides government. The child is not a creature of the state. Peter Stockland: I would not break the law, but if I had a child or children at Loyola in Montreal I would certainly use the courts to combat the Quebec government's unlawful abuse of religious freedom that forces even private Catholic schools to teach the ethics and religious culture course. Howard Voss-Altman: It is difficult to imagine such a scenario. As a Reform rabbi, our movement prides itself on being both Jewish and modern, able to embrace the scientific world, and more importantly, a pluralistic world that recognizes many different paths to truth and enlightenment. If our children were faced with the prospect of, say, a neo-Nazi teacher, then we would certainly keep our children home until such teacher was suspended and/or terminated. But that hardly rises to the level of breaking the law. If we are discussing civil disobedience regarding a political or social issue, then of course I would consider breaking the law to protest the unjust law. But it's hard to imagine such a law that would impact our ability to parent our children. Guy Nicholson: How strongly do you feel about passing your faith on to your children? Sheema Khan: My husband and I feel very strongly about teaching our children the foundations of our faith, and living the faith as fully engaged citizens. We believe that a moral framework is essential for healthy development of our children, which serves as a foundation upon which to build their character and identity. This moral framework also includes respect for the dignity of all of God's creation – the human family, animals, the environment and so on. It includes a commitment toward principles of justice (do unto others …) and compassion. Of course, in the end, they will make their own choice, which we hope will include adherence to Islamic principles. However, there is no guarantee. Each person has been given the faculty of choice. Peter Stockland: I cannot imagine failing to raise my children in our faith. Of course, there comes a time when they must choose which faith, or none at all, to follow. But if you are a person of faith, my strong belief is you are denying your children authentic choice unless you provide a foundation in childhood. A strong foundation. Howard Voss-Altman: I feel very strongly about passing the Jewish faith on to my children. However, such faith is passed on through moral teaching, home observance, attendance and participation in the synagogue, and of course all the cultural and ethnic education that is available to them. If parochial school becomes the conduit for passing on our heritage, we have not fulfilled our role as parents. Lorna Dueck: I felt that was very important, but in saying that, I mean I wanted to educate my children in a way that encouraged them to examine the evidence for Christianity, hear the stories, watch the lives and fruit of faith and think this through. We're not making robots out of our children, indoctrinating them, but rather, the more they get to know the world, the more they will get to know their need for Jesus. I took Scriptures seriously on this. There's a passage where Jesus tells his followers, "Let the children come to me. Don't stop them! For the Kingdom of Heaven belongs to such as these." That innate spirituality in my young children challenged me – and kept me on my toes trying to respond to their curiosity. They are young adults now and I have not asked their permission to write about this – sorry, kids. Peter Stockland: I wonder if others would agree that it is important, too, to teach our children that there are things we believe are true. We believe in our faith precisely because we believe it to be true. Anything else would be an absurdity. Guy Nicholson: Have government and secular Canadian society been too intrusive in telling us how to raise our children? Or what about the other sides of that coin – have religious leaders been too intrusive in telling us how to raise our children? Have religious people been too intrusive in telling others how to raise their children? Peter Stockland: Without question, in my mind, the state and what we consider society has been far too intrusive in this regard. And the resulting pushing of religious faith into the purely "private" sphere has dangerous consequences. Sheema Khan: I think our society is a little sensitive about religion in the public sphere. That is, we are expected to keep our faith private, unassuming and hidden. While there can be merit to some aspects of such an approach, I believe that it stifles the natural inclination of those who simply live their faith naturally, openly, without any desire to convert others. I lived in the United States for seven years and of course their approach to religion in the public sphere is completely different. It is an inherent right to express your religious beliefs, provided you do not harm others. Of course, the state has no right to favour one faith over another. Yet, one can freely express one's faith. Here, I find that type of natural freedom is tempered. I'd like to know where this comes from. Howard Voss-Altman: Our experience has been that the school system appears to reflect a healthy, diverse, pluralistic approach to the world. Science is emphasized at the expense of religious dogma, and modernity is emphasized at the expense of superstition. This seems to me a healthy, respectful Canadian approach to raising children in a multicultural world. I don't have the sense that any side is particularly intrusive with respect to the transmission of values. On a personal note, however, I do believe (with my tongue in cheek) that Canadian children are, on the whole, far too polite. Every so often, it's good to have a vocal disagreement. It keeps things interesting. Peter Stockland: I would respectfully disagree with Howard that the Canadian school system is diverse and pluralistic. It is increasingly unitary in its aggressive secularity that compels worship of the state, the state and nothing but the state. Sorry if that is impolite. Howard Voss-Altman: Not at all. I believe that our school system reflects a desire to create proud, civic-minded Canadians, who are able to participate in society in an intelligent and productive fashion. I believe that mission includes the right – and profound importance – of dissent, and that our teachers are indeed transmitting those values. We might be saying the same thing, but we have a different perspective as to its relative value. Peter Stockland: Or you don't live in Quebec. 🙂 Lorna Dueck: An interesting example of this tension is playing out in Ontario's anti-bullying legislation, Bill 13. Religious parents agree we have to do more to stop bullying, and that seems to be covered in a private member's submission, Bill 14. Bill 13 addresses the same issues and generated a firestorm of controversy with its overt focus on the LGBTTIQ [Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Transgender, Intersex and Queer] equity agenda. The complaint I hear is that there would be penalties for pulling your child out of those classes (those equity education classes are different than sex ed classes). So here's a fresh example where parents who want to raise their children to follow their beliefs are wondering: Will my child be penalized for voicing moral discomfort over LGBTTIQ? Christian parents should teach their children to love and accept all who self-identify in LGBTTIQ realities and protect them from bullying. But parents fear that Bill 13 will give school authorities the licence to enforce rigid ideological conformity. In the name of tolerance, alternative views could be suppressed. That takes us to Canada's original conflict over religion and gay issues in elementary schooling – the 2002 Chamberlain v Surrey School District No. 36 case. I liked how Supreme Court Justice Charles Gonthier summarized the dilemma: "Why should religiously informed conscience be placed at public disadvantage or disqualification? To do so would be to distort liberal principles in a … feeble notion of pluralism." The Bill 13/14 controversy is a government-induced conflict that religious leaders warn could trigger expensive lawsuits, publically funded ones, for years to come. Activists warn that this is a case where religious parents are too intrusive. Love will have to win the day – that's the religious definition of tolerance. Sheema Khan: I think it is important as parents, that we actively engage with our children about faith and the challenges that they face. If a child is secure in who she or he is, then that person is able to negotiate an increasingly complex world with confidence, rather than fear. I would hope that the framework of faith that my husband and I provide our children enables them to chart their own path with wonderment, humility and a sense of responsibility to make this world a better place. Howard Voss-Altman: Yes, it has. Thank you for a beautifully written response. Lorna Dueck: Whether it's public prayer, or disagreeable ethics, we all have to learn to listen to one another. If we do share our deepest convictions with each other, we should expect controversy, it shouldn't mean that at the end of the day our kids can't play together. Healthy democracy can handle this. Guy Nicholson: That's our time for today. Thanks to all for an interesting discussion.

February 9, 2012

Cardus at Centre City Faith-Based Stakeholder Engagement

On Tuesday, Cardus joined a Centre City Faith-Based stakeholder engagement in Calgary. Read the Centre City Talk blog on it and see event pictures here .

February 9, 2012

Cardus researches value of Christian education

February 1, 2012

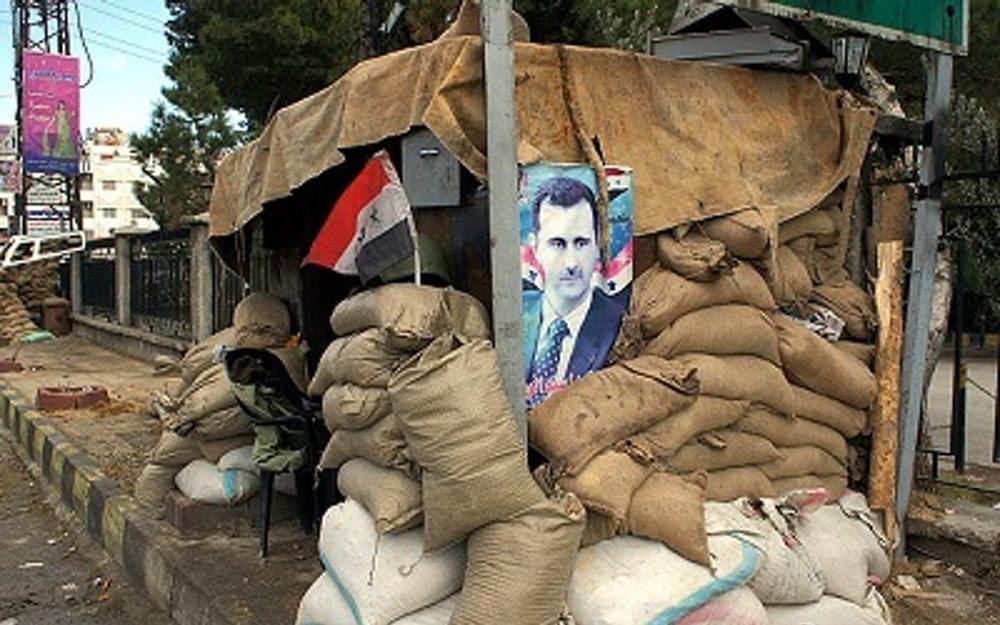

Seeking justice for Syria

On Saturday, the Arab League finally recused itself from what had become a perfunctory observation of atrocities in Syria. At least 80 people were killed in recent days, and the United Nations estimates that at least 5,400 people have been massacred by the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in the last 10 months. Is it time for military intervention? Could Western Christians justify such involvement? Should they be calling for it? The Arab League’s Secretary General, Nabil Elareby, blamed Damascus for the spike in bloodshed, saying the regime has “resorted to escalating the military option in complete violation of (its) commitments” to end the crackdown. He said the victims of the violence have been “innocent citizens,” in an implicit rejection of Syria's claims that it is fighting “terrorists.” Backstopping this criminal tyranny is Damascus’ rejection of the Arab peace plan and, more significantly, Russia’s threat to veto at the U.N. Security Council to protect Syria. And still, though it seems a callous and brutish thing to say, there is no just case for intervention in Syria - yet. Hope lies in the unification and recognition of a fractious Syrian resistance. A just intervention, or a just war, is an ancient inheritance of Christian political thought, from Augustine, through Aquinas and forward. Christians have always struggled with the twin moral call of charity balanced by the realisms of their day: what can practically be achieved, with limited resources, in often tragic circumstances. Just war is a way of faithfully calculating a terrible process of global triage. And just war demands, a la jus ad bellum, that the justness of an intervention, of any military action, must be judged not merely on moral outrage, right and true as that outrage may be, but on the probability of success and the exercise of prudent proportionality. Justice can never be predicated on short-term sentimentality. It must have a long game. The long game in Syria looks bad, maybe worse, after intervention than before. Parallels abound between Libya and Syria, but Syria is not Libya. Syrian opposition is divided and weak. Unlike the Transitional National Council in Libya, which gained fast international recognition, the Syrian National Council (SNC) took seven months to form and has received almost no recognition. The fracture is endemic in mixed calls from the SNC for Western intervention, first in favor, then denounced, then called for again. The Free Syrian Army (FSA), an armed resistance, has on its own terms called for a Western campaign. It is not the only armed force. Scores of rebel brigades, not beholden to either the FSA or the SNC, struggle on in the urban jungle of Syrian resistance. There is no front line between opposition and Assad forces that can be separated by air power, no armored columns driving along empty desert roads to be targeted by the West’s deadly drones. Syria’s killing fields are dense urban environments, nested in a region with extremely high probability for spill over into Israel, Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Iraq. Syria’s staunchest ally, Iran, is in its own ill-fated game of brinkmanship with global powers over its nuclear program. Justice can never be predicated on short-term sentimentality. It must have a long game. A no-fly zone, or any exercise of air power, would mean enormous collateral damage, in both civilian lives and infrastructure. Syria’s anti-air and military generally have not defected en masse like Libya’s. And if, from the ashes of a Syrian intervention, Assad were to be overthrown, there is very little enthusiasm today that one of the many competing factions could practically dominate. More likely, fringe groups currently allied with the regime would seize control of convenient strongholds and Syria would be gripped in a civil war, becoming a harbor for Hezbollah, the Kurdistan Workers Party, Iraqi pro-Iranian forces and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, agents of which are already embedded with Assad’s feared Fourth Armored Division. Syria would become yet another proxy war zone. “Damascus has scandalized every Potemkin effort at reform or negotiation,” says Michael Weiss in Foreign Affairs. Assad will find no peace in the international system, but 23 million Syrians still might. For that to happen, before a just war or responsibilities to protect can be exercised, a galvanized Syrian opposition must take form. A post-Assad future is possible if the international community - especially the Security Council, the Arab League and the people of Syria - work to form a beachhead of goodwill for a united, globally recognized resistance. Military intervention today appeals to the soul, but not to the senses. This doesn’t mean ignoring a slaughter, but it does mean working prudently, multi-laterally and - especially - indigenously to support, not manufacture, a united cause of Syrian freedom.

January 29, 2012

Brinkmanship with the Desperate: Now is not the time to attack Iran

Monday’s announcement by the European Union to embargo Iranian oil further hamstrings an already crippled Iranian economy. Iran is a country, argues Fareed Zakaria, growing in desperation. E.U. oil imports represent 600,000 barrels per day, or 26.3% of Iranian exports (WSJ). The game of brinkmanship in the Strait of Hormuz, between forty thousand U.S. troops stationed in the Gulf, accompanied by strike aircraft, two aircraft carrier strike groups, two Aegis ballistic missile defense ships, and multiple Patriot anti-missile systems is a badly fated gamble. It gets worse. Read the rest of the article at Capital Commentary.

January 27, 2012

Who will replace “the church ladies”?

Mark Forsythe of CBC Vancouver's B.C. Almanac plays a pre-recorded conversation with Cardus Director of Research Ray Pennings, on the declining civic core of volunteers. Listen to the clip here:

January 27, 2012

Cardus Education Survey

January 19, 2012

Media Contact

Daniel Proussalidis

Director of Communications