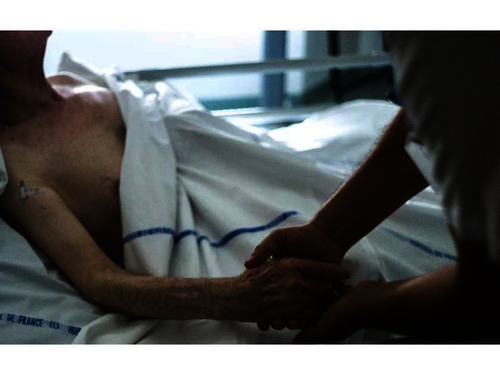

In Canada’s fragile discussions around end-of-life care, three statistics lie submerged in the rhetorical tension, dissension and fear. The first two numbers are from a 2013 Harris Decima Survey and a 2011 report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. They show, respectively, that 75 per cent of Canadians would prefer to die at home, and that 70 per cent of Canadians instead die in hospital. The third number is from a new Nanos Research poll commissioned by Cardus, which showed that 73 per cent of Canadians fear their end-of-life wishes will not be respected in whatever setting they pass their final days. A conclusion: Almost three-quarters of Canadians are not getting what they want from the care system set up to usher them over death’s threshold, and while living are denied peace of mind. This is no reflection on the skill and best intentions of those on the front lines or in the administrative roles of that system. Rather, as the Cardus report on re-framing the end of life conversation in Canada makes clear, it is a function of a system that has many overlapping, and frequently contrary, approaches and objectives. History is partly to blame. We are in a third “zig” of the zigzag that occurred during the 20th century. Through the 1930s, fewer than 30 per cent of Canadians died in hospital. By the 1950s, that had climbed to more than 50 per cent. A peak was reached in 1994 when 77 per cent of us breathed our last in a hospital bed. That was the apex of what can be called the medicalization of death. The end of life ceased to be a moment of passage, and became a test of medical perfectibility. Tools, technique and transfer of patients to ever more specialized hospital wards crowded out the family at the foot of the death bed at home. In part, economics and demographics made the move to medicalized death unsustainable. We are now living a return to older ways of saying last goodbyes. While the greying of the baby boomers, and the immense social cost of their boundless sense of entitlement, is a familiar story, something much more is behind the return to seeing death as a natural process. Modern medicine has provided us the means to mitigate much of the pain experienced at the end of life, and we can deliver it in homes and hospices as well as hospitals. Our challenge is that most health-care programs exist as stand-alone offerings rather than as a seamless continuum of care. Those confronting end-of-life issues require not only medical support from the health-care system, but emotional and spiritual support as well, including for caregivers. It’s critical to this continuum that caregivers be placed at the centre. Policy must be designed around their needs. That, in turn, requires a renewed understanding of natural death as a good and proper end of life dependent on the whole of our social architecture: family, local institutions, community in it fullest sense. Fittingly, hope for a successful transformation of our approach to death comes from what happened with life’s other inevitability: taxes. Starting in the mid-20th century, successive Canadian governments made incremental changes to the tax system to give Canadians greater control over their retirement savings. Such tools as public pensions and RRSPs became a common means to prepare for the future. They became a natural part of the continuum of conversation in Canada about life after work. Today, it’s time for a similar change in health care so Canadians have the power to plan early to ensure supports are in place to die a natural death.

Opinion: A continuum of care, before a natural death

May 7, 2015

We’re sick of ‘broken’ health care

April 29, 2015

End-of-Life Care Failing Canadians

April 29, 2015

Ray Pennings on End-of-Life Poll

April 28, 2015

Budget 2015

April 21, 2015

Fraser Institute’s Deani Van Pelt references Cardus research

In a CCTV interview, Director of the Barbara Mitchell Centre for Improvement in Education at the Fraser Institute and Cardus Senior Fellow Deani A. Neven Van Pelt explained some of the economic advantages of homeschooling. In her comments, she referred to the Cardus Education Survey: "Although, for example, home school graduates weren't quite as likely to attend university following their grade 12 homeschooling experience, if they did attend university, they were more likely than any other sector to go on and get a PhD. So it seems like someone who is homeschooled ends up being 'all in.'" Find out more about the Cardus Education Survey at carduseducationsurvey.com. Watch the full interview:

February 26, 2015

Time for mature conversation about the end of life

Choice now trumps life as Canada’s political preference of, well, choice. For the first 149 years of our existence, life had dignity and deserved the fullest protection of the law. By this time next year, Parliament must codify the principle that the choice to take one’s life is a greater good than life itself. Politics still has work to do in defining how broadly or narrowly the terms of that choice will be. Still, the Supreme Court has spoken and a fundamental shift is the inevitable outcome. Given that 2015 is an election year, any solution will be presented as a compromising middle ground, although it’s hard to imagine there won’t be alienation on either side of the unbridgeable divide between the choice for life and the choice for death. The paradox is that death is the commonality we all share. While we argue over the timing and manner of its inevitable arrival, days and months and years are being squandered in preparing for, and ultimately accepting, the finitude of life on earth. Statistics show only five per cent of Canadians have had an end-of-life conversation with their doctor. Maybe that’s, at least in part, why 70 per cent of seniors don’t wish to have life-preserving treatments, yet 54 per cent will be admitted to an intensive care unit at some point. It may also be key to the Canadian Medical Associations reminders that only 16 per cent of Canadians have access to best-practice medical care. Palliative care is often the tug-of-love orphan in the life-versus-choice argument. Both sides claim to want more of it. Both use its recognized benefits to pursue very different rhetorical outcomes. Could a source of the discrepancy be the very hyper-medicalized approach to dealing with end of life issues? I’m starting to think so. I’m becoming increasingly convinced that in addition to palliative care, the gamut of enmeshed family, community and spiritual supports necessary for best-practice end of life care are being ignored to the detriment of all Canadians. It’s not an abstract or philosophical concern. Death not only claims us all, it touches those we love and know in a wide circle around us. That, surely, should make it a fit subject for public policy discussion well beyond the moment and the means. For example, employment insurance benefits provide for six weeks of compassionate care support when a family member is diagnosed with a terminal illness where the prognosis is death within six months. Six weeks. Pause for a moment or six and think about that. You just received word that your spouse has six months to live, and society offers you six weeks of support as a gesture of compassion. So, do you take it now while you come to grips with the prognosis? During the six months, when care needs will spike? At the end so you have time together? Six weeks of compassion? Surely Canadians need a robust political and policy discussion about doing better. An all-party Commons committee tried to start just such a discussion in 2011 with a 180-page report called Not to be Forgotten: Care for Vulnerable Canadians. It is filled with practical recommendations for acting on palliative care, elder abuse, suicide prevention and effective ways to lessen the need for assisted suicide. Sadly, like so much fine work done in Parliament, it was largely filed and forgotten Perhaps instead of the next 12 months being entirely heat and light over life and choice, that conversation-starter should be made available for community care, hospice, palliative care and bereavement support groups as well as in doctors offices, where seniors and vulnerable Canadians are known to go. We will have a historic political debate over wide versus narrow law-making. We can also have a mature conversation about becoming a country that prepares itself well for the end that awaits us all.

February 20, 2015

Is Catholic Social Teaching the Same as Individual Contract Theory?

It's curious when a Calvinist agrees more with a Catholic saint than a Catholic, but Brian Dijkema, program director for Cardus Work & Economics, does just that in the Fall issue of Markets & Morality. Charles Baird says that he, along with the papal encyclicals beginning with Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, “unequivocally endorse[s] some form of trade unionism.” I would like to test that assertion against what he has written on the subject of trade unions. What evidence is there in Baird’s writings for someone who hopes to discern the church’s teaching on labor unions? What is there in Baird’s written works that will shape someone’s opinion, their workplace, and maybe their actual trade unions for unequivocal support of unionism? The full PDF of this article, as well as Charles Baird's thoughts on this controversy, can be found here.

January 7, 2015

Cardus president appears on special report about Ottawa tragedy

Cardus president Michael Van Pelt was a guest on YES TV's special "Pray for Ottawa" segment last night, which also featured Stockwell Day, author Raheel Raza, and others. Said Van Pelt: When you try to get out of the horror of today, and then you listen to the prime minister, you kind of see that underneath—the seething anger under that very measured and stately tone that he was presenting today—I think what's going to happen is Canadians [...] are going to be dealing with two questions, and questions that are hard to articulate immediately. The first question is: What kind of social dynamic got us to this place? How do we construct societies in a way that either prevent or encourage what happened today? And we have to be careful with that, that we don't generalize and make assumptions about that... but it's going to be a question that resides in our minds. [...] The second question that will be asked is: What happens to the nature of the institution? Our parliament is such a great institution. Next year, 2015, we celebrate [the 800th anniversary of] the Magna Carta—that long history of developing a parliament that gives honour to you and me, allowing us to be who we are. When you have shots right in the hall of honour, very subtly but powerfully the nature of the institution loses a sense of security. [...] We need to build a confidence around this that's much deeper and understand what it is that's so powerful about this institution called parliament that we want to hold on to. The program, hosted by Lorna Dueck, is available to view online here.

October 22, 2014

Media Contact

Daniel Proussalidis

Director of Communications