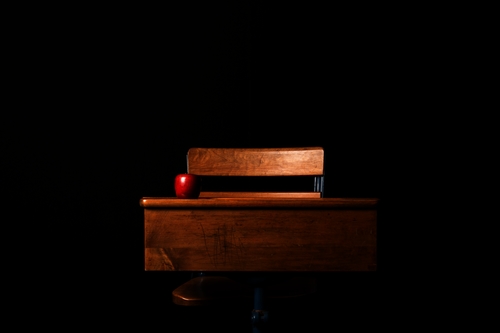

Dear College Sophomore, A lot can change in a year, right? At this time last year, you were a wary and excited freshman. Moving into the residence hall brought both the thrill of newfound independence and nervous dislocation from home and family. But you soon settled in and focused on why you were here: to learn. Sometimes going to those first-year classes felt like drinking from a fire hose. But you couldn't get enough of the new worlds that your instructors invited you into: Homer's Greece, Augustine's Rome, John Locke's England, C.S. Lewis's Oxford, Toni Morrison's Kentucky. And trust me, we noticed. You are the student that teachers dream about, the one we talk about in the faculty dining room, the one who "gets it." You didn't just treat your freshman classes as an inconvenience, the price of admission to cheap football tickets and fraternity parties. You signed up for the adventure of intellectual exploration that college is meant to be. Yet I couldn't help but notice a change in you already last spring. And now that classes are starting up again, I see a familiar shift in your stance toward the world. If the past is any guide (and it is), I worry that this is the sophomore you might become: It's not just that you're a year wiser; you carry the air of the newly enlightened. Your curiosity has hardened into a misplaced confidence; your desire to learn has turned into a penchant to pronounce, as if wisdom were a race to being the quickest debunker. You used to wonder about the social vision behind Philip Larkin's poetry, or whether Thomas Aquinas's notion of natural law could really work in a secular age, but now you seem more intent on unmasking "micro-aggressions" and detecting colonial prejudice in a canon that you increasingly disdain. I've seen it before—I see it every year. And I know where it is coming from. I know those colleagues who confuse teaching with advocacy—those colleagues who think they are broadening your horizons and opening up your world and disabusing you of your former narrowness. Teachers who delight in debunking "traditional" values that your parents espouse, teachers for whom cultural criticism consists of scoffing at anything "conservative." They were my teachers, too. I know how it feels to be invited into this exclusive club. I understand the joy ride of liberal enlightenment. But what if they're asking you to trade one sort of narrowness for another? It might feel like they're making your world more expansive, but they're actually closing it off. Dangling the badge of maturity and knowingness, they subtly replace teaching with indoctrination. Sharing the ironic distance that shores up this self-perception, they swap laughs with you in the morning about the latest takedown by Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert (wink, wink, we are the ones who know how things really work!). Unlike during those first few months of freshman year, your thinking on almost any subject now is becoming easy to predict. The causes you're passionate about, while not without merit, are almost clichéd. You seem less interested in mining the complexity of problems and more interested in making a hasty display of moral outrage and coming down on the correct side of any debate—because of course there's only one right way to think. That didn't used to be the case. Last fall I could see the wheels turning for you. I could almost sense when your mind was swirling with discovery, entertaining unfamiliar ideas, forging a sense of yourself and your commitments—questioning some prior beliefs, to be sure, but with a sense of maturing conviction that didn't shut itself off from reality. You were coming to appreciate both the complexity of the world and the range of wisdom available to us from our forebears. That's a laudable posture, not just for college but for life. So don't buy the story that the really smart people on campus are the ones who parrot the platforms of progressives. Bring a little suspicion to those who delight in their hermeneutics of suspicion. Punch through the posturing and self-congratulation and ask the questions you were asking last fall—the ones that forced me to consider my own thinking anew. You're too smart to settle for ideology, and it's too soon to stop learning. We're just getting started.

Has anyone seen last year’s promising freshmen?

August 15, 2014

Milke and Van Pelt: Why private schools should receive equal funding

In a liberal democracy, where critical thinking is often touted as an end goal in education, it was disappointing to read Calgary MLA Kent Hehr’s attack on parental choice in education (“Private schools divide pupils by wealth and religion,” July 26). Hehr’s arguments ignore the benefits of school choice and the underlying reality about how human beings function. He thus overlooks why choice is invaluable in education — because it leads to human flourishing. By not going deeper, Hehr, also the provincial Liberal Party’s education critic, thus repeated the tired and misleading clichés about independent schools. They’re for rich kids and religious kooks (although Hehr is too polite to phrase it that way). The concern over faith is misplaced. The point of a free society is to ensure diverse viewpoints are protected and encouraged — even when others disagree, especially in the education system, lest stultifying non-critical thinking become the norm. Hehr is also wrong on the facts. He fails to consider the research evidence that non-government schools provide solid, and in some cases exemplary, academic, social and cultural results for individuals and for society. A 2013 OECD analysis of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) math performance scores found that Canadian 15-year-olds from private schools significantly outperformed their peers from public schools. This was true even after controlling for economic, social and cultural status. A 2012 study by Cardus compared graduate outcomes for Canadian adults from different school systems — public, separate Catholic, and various independent school systems. The findings were clear. Graduates from independent schools are significantly more likely than their peers to contribute to civic society — to vote, volunteer, and donate (all again, after controlling for a variety of socio-economic factors that might otherwise explain the differences). Furthermore, parents don’t just “feel” — as Hehr claims — that the public system isn’t good enough for them. In a 2007 Ontario survey on why parents choose private schools and in a 2009 analysis of stories told by parents about choosing private schools, many reported that they have tried public schools for their children but were forced to look elsewhere. They leave public schools for a variety of reasons: bullying, lack of teacher care or availability, concerns with the curriculum, neglect of their child’s special needs, or poor academic results. And many stay with a private school once they arrive because of caring and attentive teachers, positive academic performance, safety, and improvements in their child’s social life. Hehr argues that any education spending for independent schools misdirects “government resources.” Such “government resources” are also known as the tax dollars of every parent. And Hehr asserts their money can only be spent on so-called “public” institutions. If that same standard were applied elsewhere in government, welfare recipients would be forbidden from spending their taxpayer-funded income at private grocery stores — only government outlets (if such stores actually existed). The point, of course, is not private or public provision but to ensure that everyone has an abundance of food to eat or is abundantly educated, regardless of who provides the food or the education. Hehr, and other like-minded allies, ignore the effect of monopolies on human behaviour and on the service to be delivered: Little innovation, sub-par service, few reasons to improve, and the misallocation of resources. For example, extra education tax dollars are often funnelled to people entrenched in the system, without improving the quality of education. The 2007 special payment of $1.2 billion into the Teachers’ Pension Plan in Alberta to make up for yet another shortfall is a perfect example. Hehr needs to think more carefully about how governments can create educational equity. It makes sense to recognize the results achieved in independent schools. When local communities are given more control — whether independent or charter schools, home-based educational programs, or public schools given more local authority — administrators, parents and teachers can achieve excellent results, results that benefit individuals and society. A system where all taxpayer dollars are spent on one provider, the “public” system, and not among the schools that parents choose, would be rejected as absurd and unhelpful if we were talking about welfare payments and grocery stores. It’s only in education — and regrettably, the mind of a provincial politician — where, despite evidence to the contrary, political attachment to monopoly thrives.

August 3, 2014

The Myth of Suburban Monochrome

A lot of Canadians live in suburbs. Conservative estimates suggest that somewhere around 21 million Canadians live in areas characterized by detached homes on large lots serviced primarily by automobiles. This arrangement is our dominant built form and is a powerful force shaping our lives. The pop culture stories we tell ourselves about suburban life are, of course, imported from the US and include themes of housewife desperation, teenage purgatory, complicity in global warming and careless consumption. Certain critiques imply that the only redemption possible for suburbanites living in such banality is to migrate to a rural area and raise free range chickens—or move downtown, put on hipster shoes and buy a transit pass. But with only a small minority of Canadians currently living in rural or urban core areas it is hard to imagine what such a mass migration would look like. Most of us don't live in high density areas and are not likely to do so anytime soon. Read the rest of this article on The Municipal Information Network website.

July 23, 2014

Bricks and Mortar Masters

I remember watching 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time and feeling that slow but steady building of dread as Hal, in his even and increasingly creepy voice, began to draw his digital noose tighter and tighter around the crew of Discovery One until a sole survivor is left. There is much to be said about what has become one of the most influential films of all time. I only want to say that the idea of technology meeting us directly as Hal does the crew is our typical vision of how what we make might indeed begin to try to make something of us. While we worry about robots taking over the world (one of my favourite genres—I commend you to the very aptly titled Robopocalypse if you need a summer read and perhaps sometime in the future a summer movie to watch if Spielberg can get the money together), we would be as well served to worry about how the design of our buildings, neighbourhoods and cities shapes the way we interact. We think less often about how other forms of technology play their shaping role among us. Some of those very non-Hal agents that we live with are the offices, houses, schools, and other buildings arranged across the landscapes of our communities and cities. Here is a proposal: What if we thought of our buildings as part of the population of our lives? I'm not suggesting they are alive in the way that Hal was (though Robopocalypse shows how that might happen). Christopher Alexander has estimated (Vol. 2 of his remarkable The Nature of Order) that there may be about 2 billion buildings in the world. If we round off human population to 7 billion, then there are roughly four people per building. With a 50-100 year renewal, we need to build about 30 million a year to keep up. Alexander points out that with 500,000 architects globally, each would have to build 60 per year. That is of course very interesting in itself and reflects that most buildings are not designed by architects. But I digress. We have among us, around us, between us, a population of agents that is very numerous indeed. Spaces within and between buildings define significant aspects of our experiences as a human civilization. How much can we actually shape our space? Very often, very little. Most of us are lucky if we can personalize our workspace or decorate a room or two in our homes the way we like. But, then, how much does space influence socialization? Don't we socialize in spite of space? We just find a way, a place. Certainly that is true. But we might consider what William Whyte showed us in 1979 via his study of how we humans use plazas in cities. His “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” is highly instructive and often very humourous (I want to thank Greg Spencer (Munk School) for reminding me in a very recent coffee conversation that the film remains worth watching). I don’t think that buildings boss us around completely, but the ways we design space, right down to some rather small details, are clearly active agents in shaping our human lives. The play area that looks like a construction site featured early in the film is hilarious—we would never allow it today with our McPadded and legally sanctioned safe (translate: boring) playgrounds. Some of Whyte's insights are that people sit where there are places to sit. If there is no seating in a plaza, there is much less socializing. They calculated it as 1 sitting place for every 30 square feet of plaza. It was also observed that socially dense areas get denser, we like the comfort of a herd, even if we don’t know the people in it. We also like corners, ledges, double wide benches and moveable chairs, even if we move them in weirdly random ways, we just want to be able to tweak a space before we commit. There are many other insights and significant amounts of other research have run down the path of humans and our relationship to spaces, I just want to say that our buildings are not in total control but they are far from non-factors in our efforts to build human connections and deepen community. In his book, The Nature of Place, Avi Friedman adds his own insight about needing human places to eat, to meet, to read and to pass the time. When the shaping of those spaces comes from large organizational entities like planning departments, courts, or government regulation, it is well worth asking if those larger processes enable us to adequately assert what we need together rather than just what the codes and structures need. Friedman notes that the first set of comprehensive zoning bylaws enacted in Canada occurred in Kitchener, ON, in 1924 under the guidance of Thomas Adams and Horace Seymour. How have such embracing directives changed the dynamic between our human societies and the society of buildings and spaces that structure our interactions? A great, deal and in rather complex ways, I would suggest. A final anecdote. JG Ballard wrote a novel in the 1970s called Concrete Island which I recently read. The premise is that a successful architect goes off the road in his Jaguar and ends up stranded in the space created by three large highway structures. Once there, the isolation enforced by what has been built profoundly changes the shape of Maitland’s life. Though passive in one sense, in another he becomes the Robinson Crusoe of car-saturated modernity. The space was far from neutral, even if it was not exactly fully in control of what happens to Maitland and can’t be held responsible in the way a human agent might. So, while our buildings may not be the boss of us, we would do well to attend to the role of our 2 billion silent citizens who do play a role in shaping who and what we are.

June 20, 2014

Dijkema in National Post: Get rid of Ontario’s closed union shop

Now that the Ontario election is over, Queen’s Park needs to act decisively to find as many means as possible to stem the flow of red ink from Ontario’s books. And while there will no doubt be heated discussion about where to find these savings — whether through cuts or attrition — there is one major policy change that is hiding in plain sight that could save anywhere from $190-million to $283-million per year. This policy change wouldn’t require new investment. In fact, it requires the government to do almost nothing except bring its procurement practices in line with those of almost every other province and developed country. Actually, it’s even simpler than that: Ontario’s government and its major cities can save money just by bringing construction procurement in line with what its own laws, guidelines and practices already require. Despite such requirements, cities such as Toronto, Hamilton, Sault Ste. Marie — and now the Region of Waterloo — take construction-project bids only from a limited pool of contractors who are affiliated with a particular union. In other words, workers and contractors can be shut out of bidding on hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of work because they exercised their basic freedom to associate with someone other than the particular union that holds the monopoly. In 2012, the Hamiton-based Cardus think tank discovered that over $900-million dollars per year was tied up by such monopolies. The unions that benefit from the monopoly suggest that the cost increase is a modest 2%, while other estimates suggest it is an order of magnitude higher. Cardus’s forthcoming paper, Evaluating Closed Tendering in Construction Markets: the Need for Fairness and Fiscal Responsibility, covers a wide range of empirical studies on competition in government construction procurement. These suggest that Ontarians are paying 20% to 30% more for construction projects that are subject to closed tendering. That means that every time a water treatment plant is built in Hamilton, Toronto, Sault Ste. Marie, every time carpentry work gets done in the Region of Waterloo, taxpayers are paying 20% to 30% too much. There is absolutely no justifiable reason for this. As we note in our paper, it is universally acknowledged that public procurement is intended to serve “the good of the general public, as contrasted with the particular individuals or firms involved in a decision.” In fact, the importance of competition is so universally accepted as the best way to attain value for the public that Ontario’s law, and all of its procurement guidelines, supposedly require it. Take the Ontario Municipal Act: “Municipalities shall not confer on any person the exclusive right of carrying on any business, trade or occupation.” Or, take Ontario’s Broader Public Sector Procurement Directive, which also mandates open, competitive bidding. The reason that directives and laws like these are in place in all OECD countries is that there is a consensus that competition creates the best value for the government, and minimizes the possibility of corruption. As we note in our paper, the structural framework for bidding on major municipal projects in Ontario is analogous to those that, in Quebec, led to the culture of corruption traced in the Charbonneau Commission’s interim report. Premier Kathleen Wynne has set an ambitious goal for her government: to balance Ontario’s budget without making cuts. Allowing Ontario municipalities, school boards, and other public entities to fall in line with what is already mandated by the province will help her accomplish that.

June 20, 2014

Milton Friesen: How Buildings Boss Us Around

Social Cities director Milton Friesen wrote about how much design matters for The Seekers Journal, a publication from the Tamarack Institute. Some of Whyte’s insights are that people sit where there are places to sit. If there is no seating in a plaza, there is much less socializing. They calculated it as one sitting place for every 30 square feet of plaza. It was also observed that socially dense areas get denser; we like the comfort of a herd, even if we don’t know the people in it. We also like corners, ledges, double wide benches and moveable chairs, even if we move them in weirdly random ways. We just want to be able to tweak a space before we commit. There are many other insights and significant amounts of other research have run down the path of humans and our relationship to spaces. I just want to say that our buildings are not in total control but they are far from non-factors in our efforts to build human connections and deepen community. Read the rest of "Bricks and Mortar Masters" at the Seeking Community blog.

June 19, 2014

Faith in the City: Part IV—American Muslims and the Civic Good

June 9, 2014

How Jim Flaherty’s reflections on D-Day speak of service

As much as any people, Canadians are justified in our tradition of treating summer as the season of hard-earned indulgence. Spend a winter in this country anywhere east of Tofino and you have won entitlement to days of warmth and ease from June to September. Yet there was a time when Canada's summer began not in stored-up indolence but in the bloodiest sacrifice a nation could call upon its citizens to make. At Dieppe in 1942 and then again on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, Canada asked its young men to run against the guns in hope of freeing the world not only from tyranny but from unadulterated evil. That, too, was part of a Canadian tradition, already embedded deep in the psyche of a country then so young, of heroism and self-giving at Ypres, Passchendaele and Vimy Ridge. Our remembrance of those events conventionally comes with the cold of November 11. But in May 2013, federal finance minister Jim Flaherty was part of a small Canadian delegation that visited European battlefields where Canadians fell, en masse, fighting for freedom in two world wars. Flaherty's recollection of the visit appears in the new issue of Convivium magazine, the publication that Calgary native Father Raymond de Souza and I oversee with the goal of fostering faith in common life. Beautifully spare and evocative, Flaherty's essay is more than an exercise in memory. It is a meditation on service so consuming it portends sacrifice of life itself. "The starkness is sorrowing," Flaherty wrote. "We are a small group—no one else is present. We walk on the beach at Dieppe where these young Canadians died. They never had a chance there on the beach, facing the machine guns above. Now we see some of their graves, row on row of individual tombstones. Some bear no name but the inscription 'Known only to God.'" Sorrowing. So perfect a word for the segue from starkness to a knowledge so intimate it belongs to God alone: the intimate knowledge of the name of the one—of the many—who fell, bloodied, for service, in sacrifice. Sorrowing. Such an Irish keening word from a man who was so proud of his Irish storytelling heritage. Was, of course, because Flaherty died unexpectedly in April, only three weeks after retiring from his cabinet post. As Father de Souza wrote in his eloquent National Post column, and expanded on in his Convivium farewell for Flaherty, the country was shocked and saddened by the loss of the minister who deftly steered us through the global financial calamity of 2008-2009. Yet from that sorrowing, from his posthumously published words, comes a call to set down at least some of the cynicism toward political service that we carry with us as the mark intellectual and conversational fashion. There is something of the unthinkable in thinking of gratitude moving from Canadians, so blessed to live in this country, toward politicians such as Jim Flaherty, who serve and sacrifice to bring our blessings to life. The majority of us, in our public language at least, seem as incapable of associating politics with sacrifice as we would be of wading ashore in the freezing waves of Normandy onto narrow beaches thanatic with gunfire. Our images of political service are invariably hyper-crowded with clichés of self-interest, self-importance and silky sinecures. The very way in which the last words of a man as powerful as Canada’s finance minister came to be published in our small magazine forces recognition of the superficiality of such stereotypes. Father de Souza and Flaherty fell into conversation last year during a mutual airport stopover, and the finance minister spoke movingly about the effect of visiting Normandy. As a good journalist does when a good story is being told, our editor asked Flaherty to publish his thoughts in Convivium. The minister demurred, calling himself "not much of a writer." Several months later, his text blew in over the transom bearing the simple directive: "Edit as you see fit." No communications minions massaged the message. Neither party agenda nor political ploy was presented. No hint of the globules that gum up so much of democratic life. Just stark, authentic, heartfelt words from a man, albeit a politically powerful man, addressing the matter that moved him most: service and sacrifice even unto death. We are entitled to indulge our sorrow at the loss those words convey. Yet thankfulness becomes us, too, as we remember the great and true tradition that has forever given our country life. This piece was originally published in the Calgary Herald on June 5, 2014.

June 5, 2014

Ontario needs school choice

Cardus senior fellow Deani Van Pelt has co-written an article with Jason Clemens that appeared in the National Post entitled, "Ontario Needs School Choice." "Ontario is one of five provinces that does not support parents who chose independent schools," they wrote. "These schools are often designed around a diversity of educational philosophies and arise from local communities working together to respond to identified student needs." You can find the complete article on the National Post website.

May 26, 2014

Media Contact

Daniel Proussalidis

Director of Communications